What are Play Schemas?

Have you ever wondered why your child purposely knocks over your block castle, hides in small boxes, throws their food, lines objects up or collects rocks? These aren’t ‘bad behaviours’ but rather natural developmental urges (called schemas) that suggest a healthy child.

These behaviours are not random. They are powerful clues about how your child is learning, growing, and making sense of the world.

Understanding play schemas is not just helpful, it is essential for truly connecting with your child, supporting their development, and responding to their needs with confidence and care.

The repetitive action of a schema allows a child to practice and construct meaning (building a stronger brain) until they have mastered the understanding of the schema. Being aware of play schemas helps in two ways:

- It helps parents and educators to differentiate between ‘behaviour’ vs ‘natural urges’ which move past the belief that a child is just being ‘difficult’

- It helps parents and educators to plan learning environments that support the development and mastery of schemas

To summarise, play schemas are NATURAL, UNCONTROLLABLE and totally NECESSARY urges that ALL children have at some point or another.

Understanding the Brain Science Behind Play Schemas

Did you know play schemas are directly connected to your child’s brain development? From birth to around age 7, children’s brains are making millions of connections every second. Repetitive play patterns like transporting, enveloping, or rotating help wire the brain for important cognitive skills like spatial awareness, memory, motor coordination, and even self-regulation.

When we allow children to repeat schematic play, we’re supporting:

Neural wiring for problem-solving

Emotion regulation through predictability

Body-brain integration for gross and fine motor development

So what are the play schemas I need to know about in early childhood?

A play schema is a repeated action or behaviour pattern that children engage in as they learn about the world around them. Think of it as the brain’s way of testing out ideas through action.

Common play schemas include:

Trajectory – Throwing, dropping, or watching things move through space

Enclosure/Enveloping – Hiding inside a box or wrapping toys in fabric

Transporting – Moving objects from one place to another (and filling pockets with rocks!)

Rotation – Spinning wheels, twirling around, or turning objects in circles

Each of these behaviours supports brain development by allowing children to explore physical concepts, spatial awareness, and emotional regulation.

The following list describes the most common 9 play schemas that you may have seen in your child. It is important to know that there are many more schemas than just these nine. I am sure as you read along, you’ll remember some of the moments your child was practising their schema.

Enveloping Schema

Enveloping is a highly evident schema; involving the children covering themselves or objects. This might look like wrapping toys in paper, laying fabric on top of dolls, playing peek a boo with silks, climbing into boxes or kitchen drawers, or hiding your keys in a cupboard.

Enclosing Schema

Enclosure involves drawing or creating a barrier or enclosure. It may involve connecting items to build a fence or drawing circles around objects. At dinner time this might look like moving food to the edge of the plate. The difference between the enclosing schema and enveloping schema is that enclosure usually forms a parameter/fence around the sides of something, whereas enveloping has it covered top and/or bottom too.

Connection Schema

Connection involves going objects together. It might involve taping things together, connecting blocks or lego or joining train tracks. This can mean a process of connection then disconnection also, such as building a castle then knocking it over.as we see them. We are able to provide resources and suggest activities to help develop and master our child’s play schema development. We can also shift undesirable behaviours (such as throwing food) into constructive play.

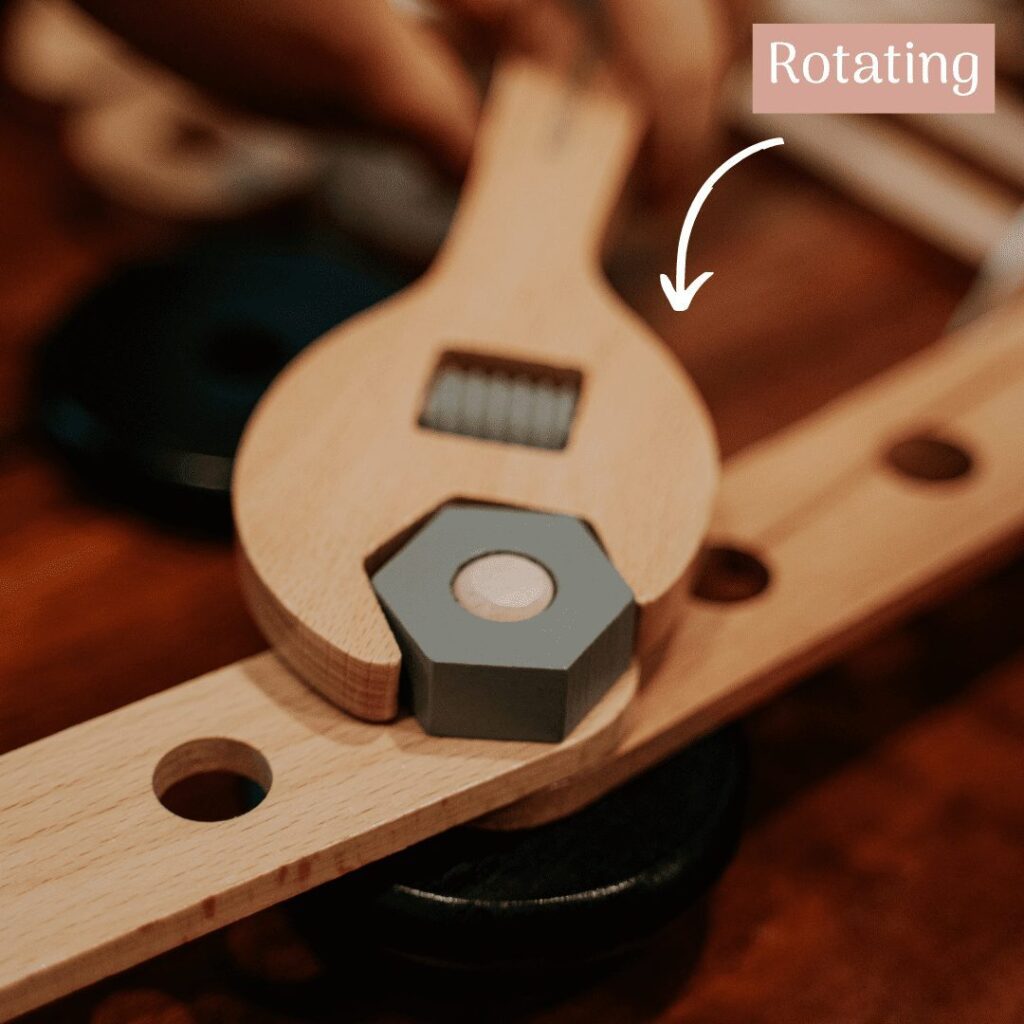

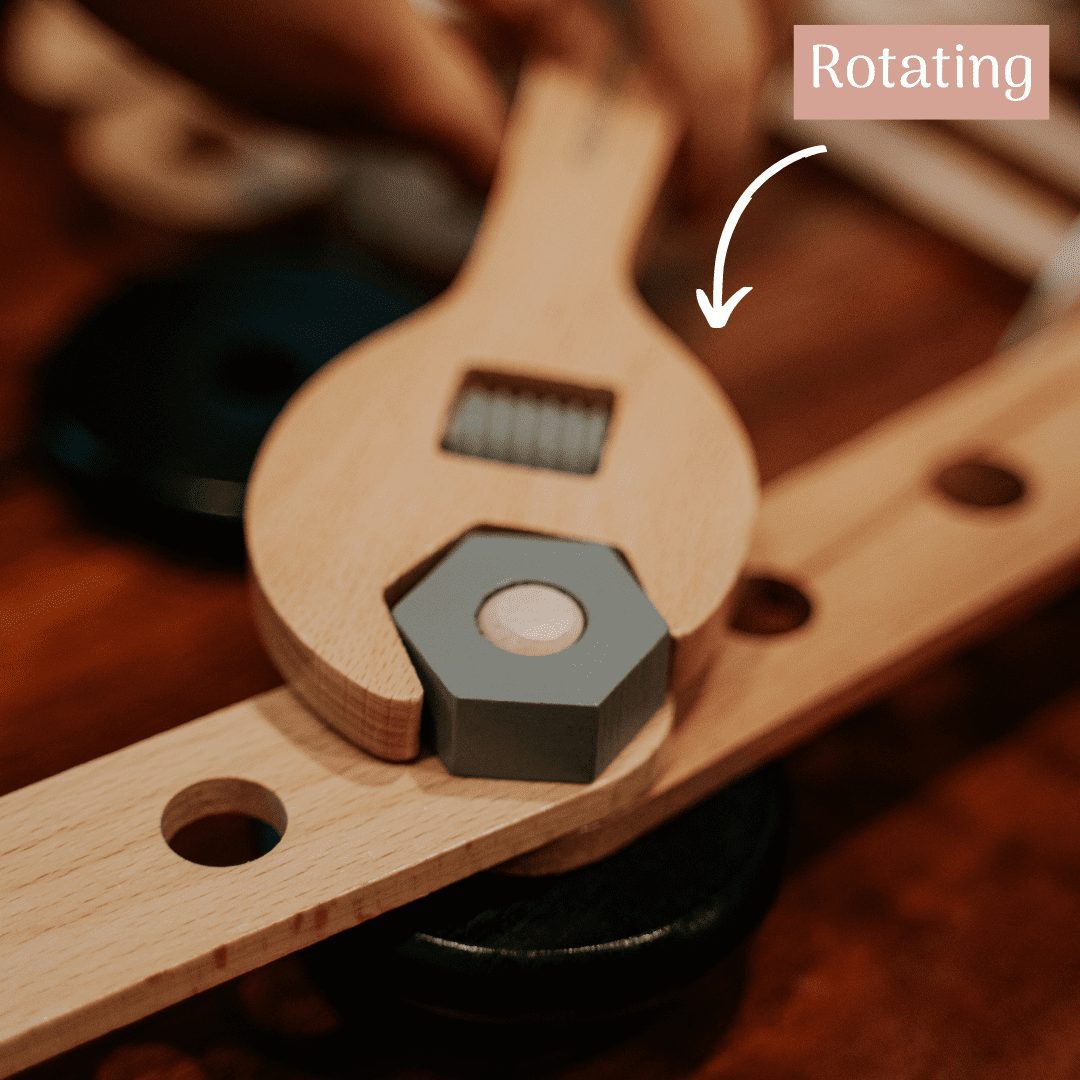

Rotation Schema

Rotation invoices spinning, twisting, rolling or turning. Children exploring this schema are generally attracted to and may benefit from things with wheels, spinning, playing ring-a-rosey, riding a bike in circles or using screwdrivers.

Trajection Schema

Trajectory involves dropping, throwing, kicking, swinging items; perhaps the most problematic schema of them all. A child experiencing this schema may drop their food at the table, throw toys, kick objects or people, enjoy swinging, or dropping things into containers.

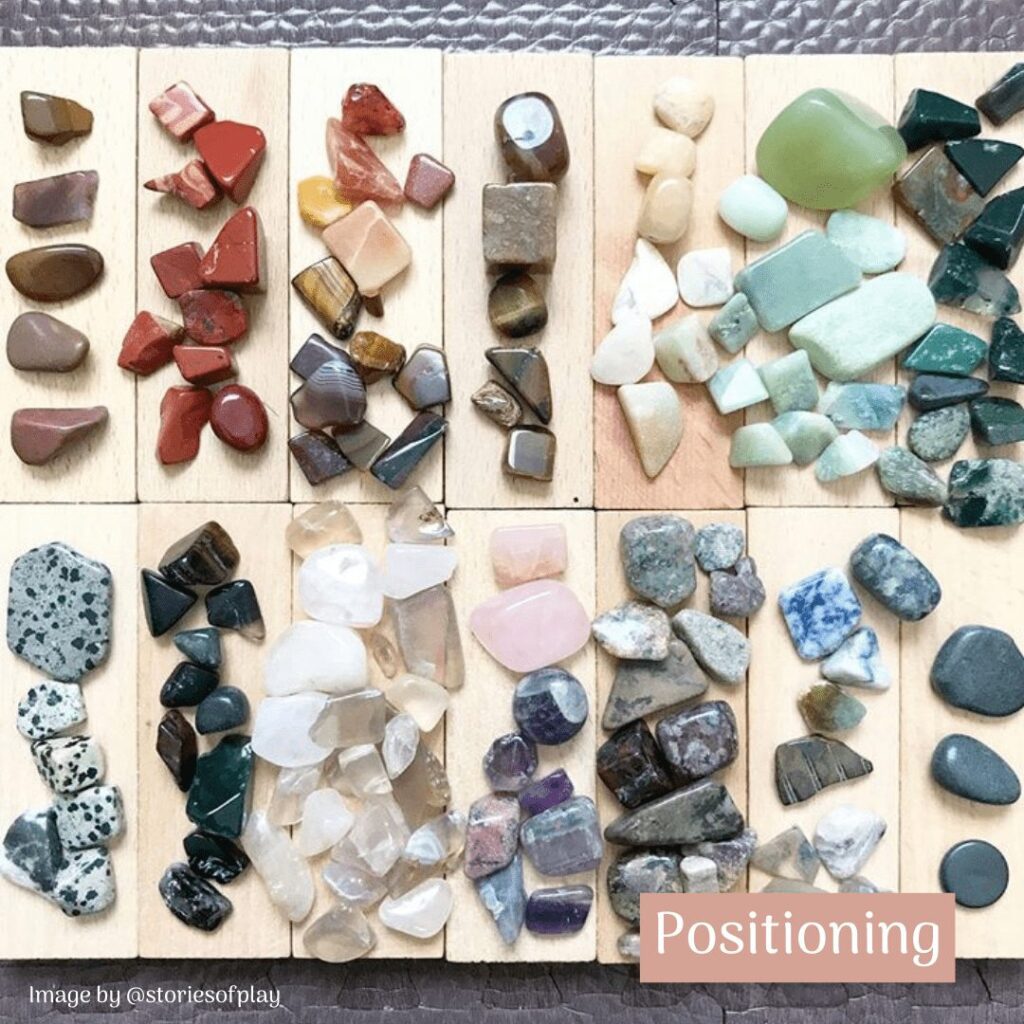

Positioning Schema

Positioning involves lining up toys, position things into order, ordering books, turning cups upside down or obsessing over items being in an exact place.

Orientation Schema

Orientation involves the child having a deep interest in seeing things from different angles or heights. The child might like climbing to irregular places, hanging upside down, looking at things side on.

Transportation Schema

Transporting involves moving objects from one place to another. A child may like to move objects using baskets, wheelbarrows, buckets, pockets, boxes or their hands.

Transformation Schema

Transforming involves changing/ transforming the state of something. It involves a visual transformation, such as mixing, freezing, drying a substance. Some examples may include a child who loves to wash their hands with soap over and over again, or the child that adds chalk to a cup of water.

As a parent or educator, one of the best things about having an understanding of these urges is that we are able to recognise and support them in our children. When we understand schemas in early childhood we no longer view behaviours as problematic, and rather as exploration of urges.

Frequently Asked Questions About Play Schemas

When should I worry about a schema becoming a behaviour problem?

If a child is being aggressive or unsafe, they may still be working through the trajectory schema. Rather than punishing, redirect them to a safe alternative like throwing beanbags at a target or dropping balls into tubes.

Can older children still have schemas?

Yes! Children up to 8 (and beyond) can show schematic urges. Even adults experience them — ever feel the urge to line your pens in a certain order or get lost in spinning a fidget ring?

How can I tell what schema my child is exploring?

Observe their repetitive play. What do they do over and over again? Keep a journal or snap photos for a week — patterns will emerge!

When and how do schemas appear?

Schemas usually become quite evident in children from around 6 months and remain visible for a few years. Generally one schema is quite strong and as mastered, will be replaced by another. However children are always practising multiple schemas at once, and not all children visually appear particularly schematic. (In fact adults indulge in schemas also, however we have mastered these skills over our life and our schemas are no longer as visible).

What is my role as an educator when viewing children through a schematic lense?

By acknowledging play schemas in children, you will be able to better inform your planning cycle to meet each individual child’s needs. Observe the schema/s being mastered, analyse the schema, plan for the schema then reflect. Experienced educators plan learning environments that support the development and mastery of schemas; thus have multiple resources available at all times.

Schema-Supported Environments: What Do They Look Like?

If you are an educator or parent wondering how to set up a play space for schematic play, here’s what to consider:

Transporting: baskets, wheelbarrows, trolleys, or open-ended small objects.

Enveloping: scarves, silks, boxes, cubbies, or large envelopes.

Enclosing: wooden blocks, train tracks, magnetic tiles or felt shapes.

Rotation: tops, spinning wheels, bikes, ball runs, pulleys.

Trajectory: safe throwing zones, balls, ramps, outdoor climbing play.

Positioning: stacking blocks, peg dolls, small counters or nature treasures.

Transformation: water play, painting, sensory trays, playdough stations.

In the next blog I explore specific resources and activities to support schematic play.

These insights are explored further in our Schema Course, designed to help parents and educators nurture development through play.

Blog Written by Amie Muir

- Bachelor of Early Childhood Education

- Master of Educational Neuroscience

At Growing Kind you can browse and SHOP our resources by each schema:

Trajection

Shop resources that support the Trajectory Schema

Rotation

Shop resources that support the Rotation Schema

Transformation

Shop resources that support the Transformation Schema

Positioning

Shop resources that support the Positioning Schema

Transporting

Shop resources that support the Transportation Schema

Connection

Shop resources that support the Connecting Schema

Enveloping

Shop resources that support the Enveloping Schema

Enclosing

Shop resources that support the Enclosing Schema

4 comments

Great explanation of repeated behaviour.

My 1year old boy tends to “fight” by hitting us in the face. Is that normal behaviour or not. Please help

yes my child does the same thing but with knifes you are lucky

The Trajectory Schema is driving my trajectory straight up a wall