What are Play Schemas?

Have you ever wondered why your child purposely knocks over your block castle, hides in small boxes, throws their food, lines objects up or collects rocks? These aren’t ‘bad behaviours’ but rather natural developmental urges (called schemas) that suggest a healthy child.

The repetitive action of a schema allows a child to practice and construct meaning until they have mastered the understanding of the schema. Being aware of play schemas helps in two ways:

- It helps parents and educators to differentiate between ‘behaviour’ vs ‘natural urges’ which move past the belief that a child is just being ‘difficult’

- It helps parents and educators to plan learning environments that support the development and mastery of schemas

To summarise, play schemas are NATURAL, UNCONTROLLABLE and totally NECESSARY urges that ALL children have at some point or another.

So what are the play schemas I need to know about in early childhood?

The following list explains some of the play schemas that you may have seen in your child. I am sure as you read along you’ll remember some of the moments your child was practising their schema.

Enveloping Schema

Enveloping is a highly evident schema; involving the children covering themselves or objects. This might look like wrapping toys in paper, laying fabric on top of dolls, playing peek a boo with silks, climbing into boxes or kitchen drawers, or hiding your keys in a cupboard.

Enclosing Schema

Enclosure involves drawing or creating a barrier or enclosure. It may involve connecting items to build a fence or drawing circles around objects. At dinner time this might look like moving food to the edge of the plate. The difference between the enclosing schema and enveloping schema is that enclosure usually forms a parameter/fence around the sides of something, whereas enveloping has it covered top and/or bottom too.

Connection Schema

Connection involves going objects together. It might involve taping things together, connecting blocks or lego or joining train tracks. This can mean a process of connection then disconnection also, such as building a castle then knocking it over.as we see them. We are able to provide resources and suggest activities to help develop and master our child’s play schema development. We can also shift undesirable behaviours (such as throwing food) into constructive play.

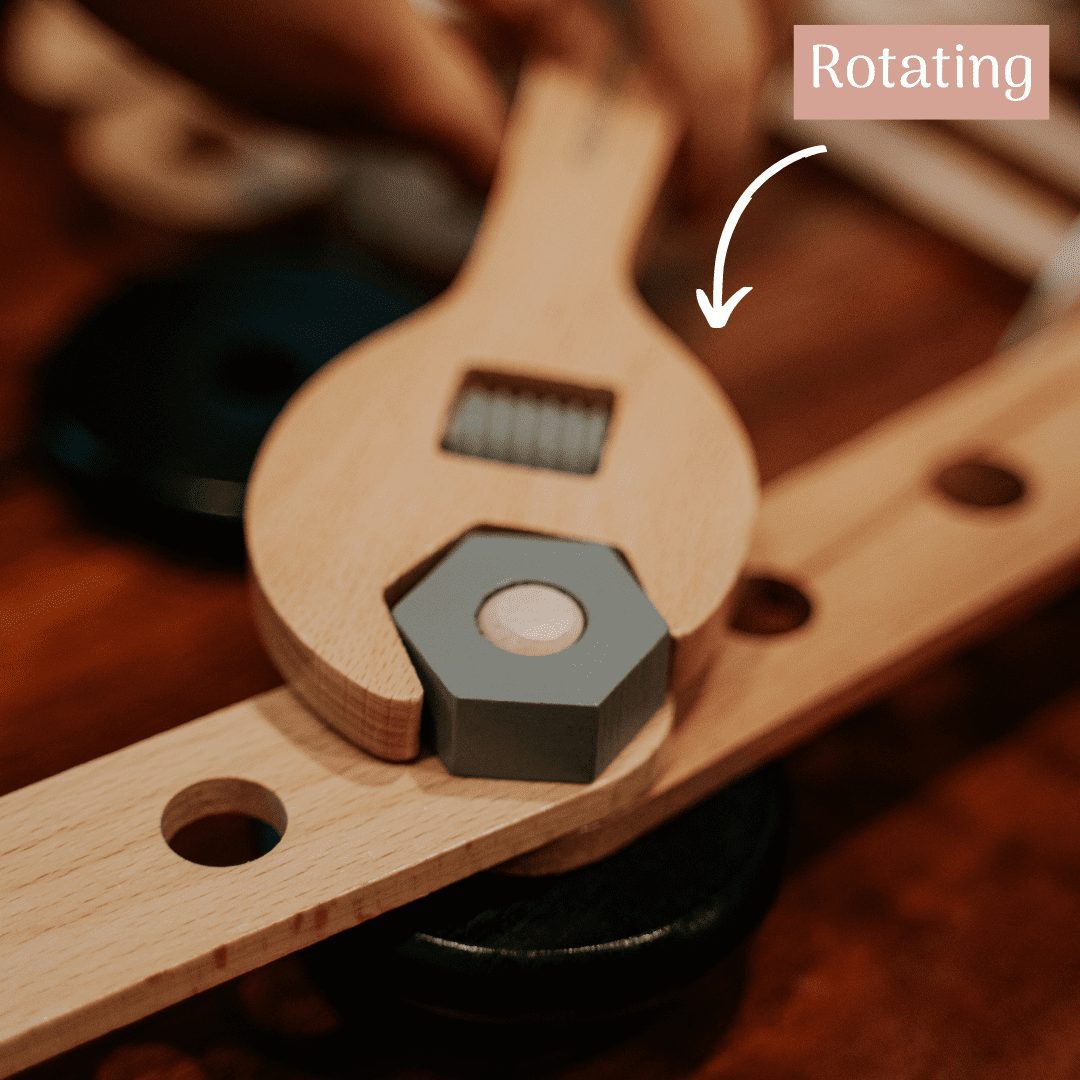

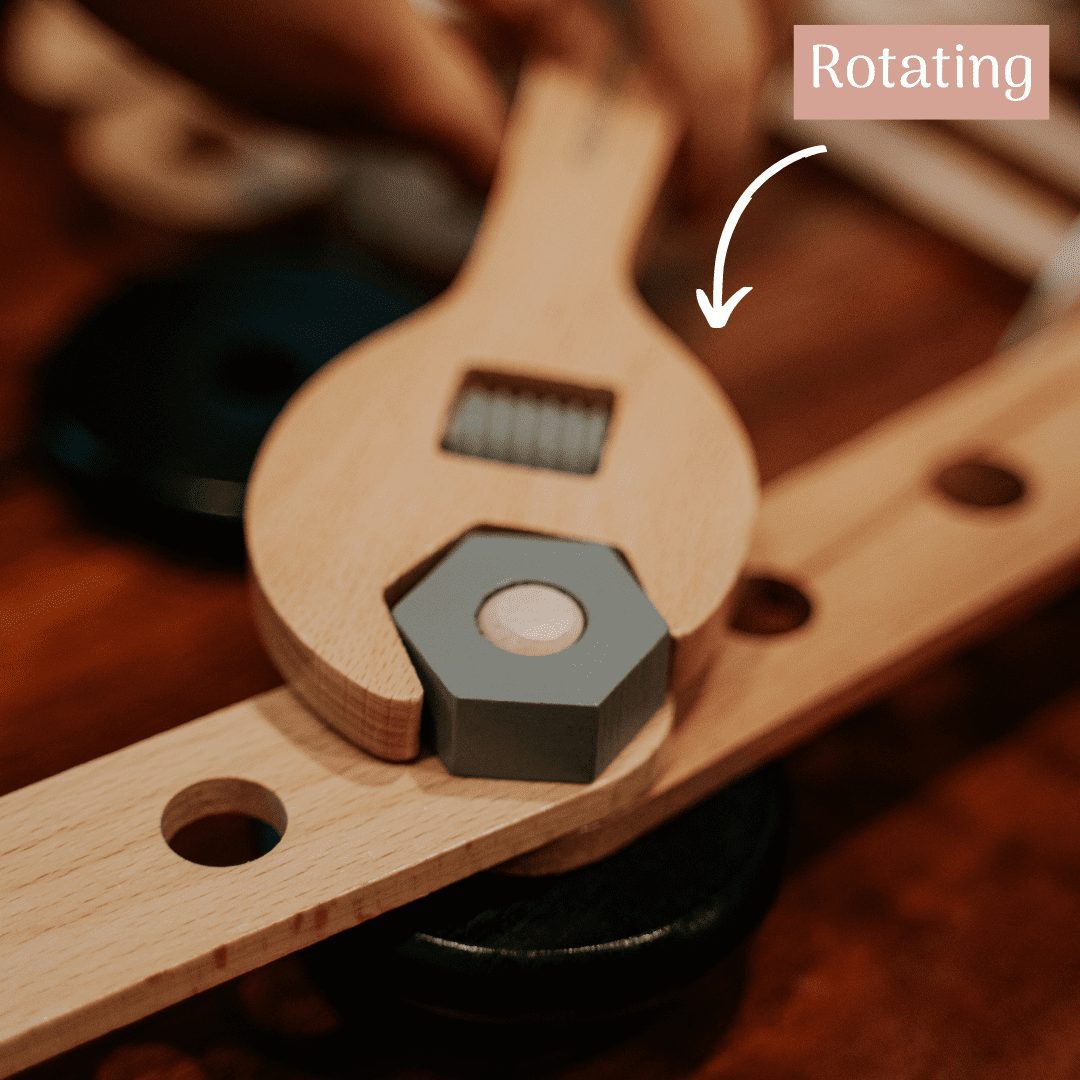

Rotation Schema

Rotation invoices spinning, twisting, rolling or turning. Children exploring this schema are generally attracted to and may benefit from things with wheels, spinning, playing ring-a-rosey, riding a bike in circles or using screwdrivers.

Trajection Schema

Trajectory involves dropping, throwing, kicking, swinging items; perhaps the most problematic schema of them all. A child experiencing this schema may drop their food at the table, throw toys, kick objects or people, enjoy swinging, or dropping things into containers.

Positioning Schema

Positioning involves lining up toys, position things into order, ordering books, turning cups upside down or obsessing over items being in an exact place.

Transportation Schema

Transporting involves moving objects from one place to another. A child may like to move objects using baskets, wheelbarrows, buckets, pockets, boxes or their hands.

Transformation Schema

Transforming involves changing/ transforming the state of something. It involves a visual transformation, such as mixing, freezing, drying a substance. Some examples may include a child who loves to wash their hands with soap over and over again, or the child that adds chalk to a cup of water.

As a parent or educator, one of the best things about having an understanding of these urges is that we are able to recognise and support them in our children. When we understand schemas in early childhood we no longer view behaviours as problematic, and rather as exploration of urges.

When and how do schemas appear?

Schemas usually become quite evident in children from around 6 months and remain visible for a few years. Generally one schema is quite strong and as mastered, will be replaced by another. However children are always practising multiple schemas at once, and not all children visually appear particularly schematic. (In fact adults indulge in schemas also, however we have mastered these skills over our life and our schemas are no longer as visible).

What is my role as an educator when viewing children through a schematic lense?

By acknowledging play schemas in children, you will be able to better inform your planning cycle to meet each individual child’s needs. Observe the schema/s being mastered, analyse the schema, plan for the schema then reflect. Experienced educators plan learning environments that support the development and mastery of schemas; thus have multiple resources available at all times.

Trajection

Shop resources that support the Trajectory Schema

Rotation

Shop resources that support the Rotation Schema

Transformation

Shop resources that support the Transformation Schema

Positioning

Shop resources that support the Positioning Schema

Transporting

Shop resources that support the Transportation Schema

Connection

Shop resources that support the Connecting Schema

Enveloping

Shop resources that support the Enveloping Schema

Enclosing

Shop resources that support the Enclosing Schema

In the next blog I explore specific resources and activities to support schematic play. Make sure you are signed up to our mailing list to find out about our latest articles.

4 comments

Great explanation of repeated behaviour.

My 1year old boy tends to “fight” by hitting us in the face. Is that normal behaviour or not. Please help

yes my child does the same thing but with knifes you are lucky

The Trajectory Schema is driving my trajectory straight up a wall